Project

A Tree Called Home

2021

All invalids (invalidu rozn´) are not equal…

At the head of the line stand the all-important invalids of the Second World War. Behind them we find the invalids of military conflict who have similar entitlements, starting with the participants in squelching anti-communist protests in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, and ending with those wounded in Afghanistan and Chechnya. Further back [in the line] are invalids of military service, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the KGB, and other “forces.” Then invalids of the workplace and those injured “at the hand of others” get their turn. Those accident victims (bytoviki), who are themselves at fault, come in last, along with the congenitally disabled, who have no one at all to blame.

Lev Indolev

Lev Indolev, a journalist and a key figure in the Russian disability rights movement. Although Indolev was writing about post-Soviet Russia, the roots of the differentiation he describes lie in the Soviet period. Lev Indolev, Zhit ́v koliaske. 2001 (To live in a wheelchair) quoted from Disability Studies Quarterly, Vol 29, No 3 2009.

Psychoneurological Internat A

A home for more than 1,000 people in Ensk, Russia. “The stated goals of the internaty were as follows: material and practical support of residents and the provision of good, ‘home-like’ living conditions; organized care for the residents, including medical care; and measures to ensure the social and vocational rehabilitation of people with disabilities. In general, internaty were total institutions, functioning as medico-social institutions intended for permanent residence of the elderly and disabled who require constant practical and medical assistance.”

Psychoneurological asylums (psikhonevrologicheskii internat, PNI). To protect the privacy of residents and staff , the actual number of the psychoneurological asylums are not specified here but instead is referred to as “PNI A” and “PNI B.” The names of the geographical places have also been changed.

Iarskia-Smirnova and Romanov 2002:325 quoted from Disability Studies Quarterly, Vol 29, No 3 2009.

Places are never neutral. Geography, politics, and identity are concepts which are interwoven with each other like the threads of an intricate fabric. What is lost in a traditional history writing? What is included, and what is excluded? How is history written? And whose history is told?

This house and the people living here, is a physical manifestation of a form of control and care by the state. Persons with physical and mental disabilites have been stigmatized, hidden from the public, and thus made seemingly invisible.

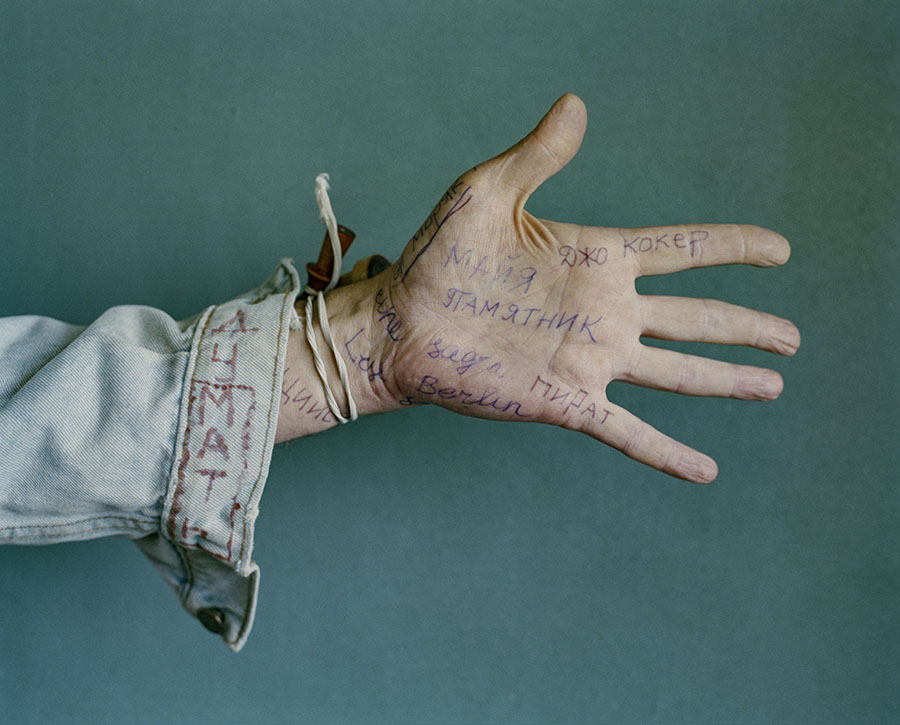

A Tree Called Home is a critical examination of a system built to house and take care of citizens who are judged to be “undesirable” in Russia. Persons with physical and mental disabilities are stigmatized, hidden from the public, and rendered largely invisible in a network of state-run institutions.

Since 2002, Kent Klich has documented the workings of one such institution that houses more than 1,000 people. He also collaborated with Aleksey Sakhnov, an artist and long-term resident whose drawings and photographs, as well as images of his papier-mâché houses, are included here. Leonid Tsoy, a psychologist who worked in the same network of institutions, contributes his study on “The Psychoneurological Asylums in Russia,” focusing on the relationships between normativity and violence. A Tree Called Home also includes an essay, “The Other and US,” by Fred Ritchin, a writer, editor, and curator examining the potentially transformative roles of the image in society.